Library Digest: Kirsteen Stevenson

A review of Imperial Intimacies by Hazel V. Carby.

Scanned Image: Hazel V. Carby, Imperial Intimacies: A Tale of Two Islands, Verso Books, London, pp. 324-325, 160-161.

Imperial Intimacies: A Tale of Two Islands, begins with ‘the girl’ – the girl who is constantly asked ‘the question!’. ‘The question’ was always lying in wait – asking her to define herself to those who placed concessions on her. Always to slot herself into other people’s understanding and alert her to how she somehow didn’t fit with others expectations of ‘Britain’. Soon she stopped answering ‘the question!’ not because people stopped asking it, but because she realised she didn’t need to explain her existence.

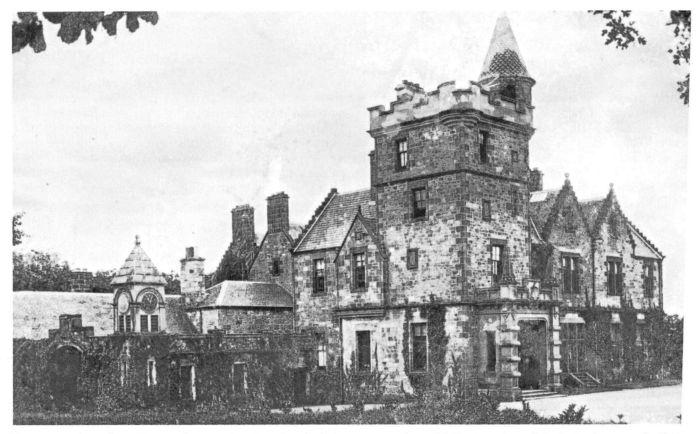

I was never asked the ‘question!’ in the same way- why would I have been? White, growing up in the North-East of Scotland, but I would have answered the same way that Hazel V. Carby did at first – responding with the name of the village where my home was. I wouldn’t have been badgered and prodded: ‘No, where do you really come from?’ Where I come from, I played in the woods as a child, building dens and imagining worlds. In these woods there is a care home for the elderly run by the Church of Scotland, a stately home with manicured lawns and grand pathways that lay through the trees; old gas lamp posts flaked with British racing green, rusted wrought iron fences and a walled garden. When I was growing up, I didn’t know that the house had begun construction around the 1830’s by a gentry family – it was always just ‘the Old Folks Home’ to me. I recently found out that the father of the man who built the home, had been given (or taken) the name, Harry Lumsden of Jamaica.

When reading a small book written on the history of the area in Aberdeenshire, I found that this family had put a lot of money into the village and this was happening all over the country during this time. Nowhere in the book did it mention Jamaica, and the money made off the exploitation of enslaved peoples there, or the reparations that were paid to those who ‘owned’ the enslaved.

These histories are overlooked because they are shameful, but also because the benefits gained from those atrocities are completely intertwined with the advancement of our modern society.

The house I grew up in, near those woods I had played in, was built after the First World War in the 1930’s, when the house and the land that the gentry had owned was sold, divided up and made into smallholdings – the same imperial technique that shredded-up plantations in Jamaica after abolition.

Credit: From Old Balmedie and Belhelvie Parish by Rosie Nicol

And so where am I from? A village in the North-east of Scotland that has been undoubtedly shaped, perhaps created, by the money generated and stolen from enslaved people in Jamaica. Britain and Jamaica have a connected history that has been influenced by the money, cruelty and accountancy of the British empire, as told imaginatively in Hazel V. Carby’s book Imperial Intimacies.

While reading Imperial Intimacies I felt that Carby was writing to untangle herself from Empire, carefully unwinding the strings of her family tree starting with her close family and personal memory then working her way out. Carby uses historical references and succinct prose to delicately breathe life into the characters and times of her family’s history, taking the reader to the places of Jamaica, Wales and England, inside the engine of a steam train, to see a viking longboat coming onto the shore or studying a piece of lichen stitched upon a gravestone. She weaves these tales to create a larger picture of empire from the inside -out.

Carby travels through her memory of childhood looking back on ‘the girl’ who escaped into books, and explored nature, daydreaming through streets in Surrey, named after Robin Hood.

Carby now sees ‘the girl’ as detached from her current self. The girl learned that the information that she was receiving from the world around her was hostile and that others placed different expectations and qualities onto her. The girl’s heritage was taken from her repeatedly; in one heartbreaking example, the girl is told by a teacher that she is lying about her father having been an RAF pilot during the war, and that no black people served in the Second World War and that Britain won the war alone – at home a photograph of her father in his uniform sat proudly on the piano.

A common lie told to its citizens is that Britain is a small island standing alone against the world, when in fact the structures of the empire seek to use people when necessary for its own interests. With a known history of drafting people from the colonies, Britain masquerades as standing brave and alone, despite being built on the efforts of others, causing ruptures and migrations in the lives of people for its own means and then rejecting those people, racialising them or using them as scapegoats for political strategy.

Born to a white Welsh mother and a black Jamaican father, both of Carby’s parents had strong memories of Empire Day as children, where they sang the same songs and waved union jacks, one in Britain, the other in the Caribbean. Both of Carby’s parents were the first to volunteer to serve the Empire during the Second World War; her mother worked for the Civil Service in London and her father was recruited for the RAF in Jamaica; they met while he was stationed in the UK. Her Mother and Father both upheld the values of the British Empire.

Carby explores the contentious reality of the outwardly racist post-war Britain she was born into, where racially mixed relationships were seen to most as a betrayal of whiteness and British identity, fostered by hostile governmental policies. These views and feelings of British society eroded her parents’ relationship, encroaching on the delicate balance of domestic life, making politics personal.

Delving further back through time Carby relives the conditions of her family history, tracing the lines of colonisation, where her ancestry and industry meet. Her mother’s side lived as workers in cities blooming with commerce and trade built from the money generated by the enslavement of people in the Caribbean, in places such as Bath and Bristol. They struggled with poverty and aspired to move upwards in society, seeing the upper classes erecting buildings and statues and schools, as working people suffered with disease and hunger. Industry thrived, but the reality and the details of how was overlooked.

While reading this book I became more aware of notions that have just always existed and been accepted as normal in Britain. The history of the empire is constructed carefully to incite patriotism in its people, certain facts may be omitted, embellished, celebrated or denigrated. The celebration of Empire Day and Coronations for those previous generations helped to engender the favour of citizens, as did the commemorative mugs and tins and Jubilee coins that were handed out for free. The adaptation of stories or particular histories help to create an idea of a generous and courteous ruling class who were rich because of their intellect, avoiding the reality of their cruelty; at home in Britain and the places they colonised.

Her father’s life in Jamaica had been overshadowed by hunger, rioting and violent revolution due to British companies such as Tate and Lyle who paid their workers ‘starvation wages’. The West Indies were neglected by the Crown Colony during this time as colonial assaults in Africa and India took priority, even as a number of natural disasters devastated Jamaica and destroyed people’s lives. Carby goes back to the time of slavery and trade in Jamaica orchestrated by the British Empire, exploring the history and plantations of her ancestors. A poignant question that was asked of Carby hangs in the air: ‘are you from the white Carby’s or the black Carby’s?’ The parallels created throughout this book are piercing and affecting, allowing historical facts to ground into a reality that have been clouded by imperial interests of segregation.

The insidious nature of the empire wields its power through ledgers, uniforms and categorisation. I don’t wish to categorise this book. It ebbs and flows like breath, like lichen, it is a mutualistic relationship that is emblematic of natural forms, that speak more to truth than the hard line of a ledger. Categorisation, the ‘great’ tool of the British Empire, takes something away from humanity, in Imperial Intimacies Hazel V. Carby expands beyond that with the nuance of her family history in both Jamaica and Britain. A tale of two islands, their histories entangled by colonialism can easily be personified by Carby’s mother and father. Tracing the lines of history from each parent, Carby creates a map of connections travelling through time and place, showing the impact of the personal and political history of the British Empire.

Credit: Kirsteen Stevenson

About the writer: Kirsteen Stevenson is a Scottish artist and writer, based in Glasgow. She is currently working on a film exploring the mechanism of memory, place and home.